Red, White and Black

NC State magazine takes a look at the campus locations whose stories hold significance to African Americans and provide a more complete history of the university.

Written by Chris Saunders

It’s hard to think about NC State without calling to mind one of campus’ storied landmarks. There’s the Belltower, of course, and Reynolds Coliseum, home to historic concerts and great Wolfpack wins. The Court of North Carolina and the Brickyard, on whose paths we’ve walked to class or stopped to chat with a friend.

NC State wouldn’t be NC State without these places and their stories. But there are other, less well-known places, that tell important stories — stories that reveal the African American experience at NC State. We collected some of them using information from the Red, White & Black Walking Tour, which ran on campus from 2011–2016, and turning to the Technician and the Nubian Message for research. Some of these places hold horrific histories. Some represent homes to communion and unity. And yet others signify the ongoing struggle for equity.

McKimmon Center

This was the site of the first Brotherhood Dinner, in 1978, held to honor African Americans whose work contributed to enhancing the community. The event was organized by Chancellor Joab Thomas and Lawrence M. Clark, a mathematics education professor and coordinator of the university’s affirmative action plan. The dinner became an annual event and would go on to honor such figures as historian John Hope Franklin, former NAACP chair Julian Bond and civil rights pioneer C.T. Vivian, who had worked at Shaw University and had helped organize demonstrations with Martin Luther King Jr. The dinner later became known as the Lawrence M. Clark University Community Dinner.

The Brickyard

Some 200 NC State, UNC and Duke students met on the Brickyard on April 7, 1968, three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., with plans to march downtown. The march came after a handful of Shaw University students marched downtown and were turned back by Raleigh police. Chancellor John T. Caldwell met the Brickyard group near Winston Hall. Caldwell used the police microphone to address the group. “I wept tears when Martin Luther King died; I loved that man,’’ he said, and then issued a warning: “But you don’t have to demonstrate by breaking the law. Make your requests and disperse, or you will be arrested.” As National Guard troops waited near the Velvet Cloak Inn, most of the group left. A few demonstrators later made it to the State House.

Holladay Hall

In 1969 another group of protesters met Caldwell, this time at his office in Holladay Hall. The meeting followed months of strife between Caldwell and university workers, who wanted female maids working in male dorms to be assigned to a different area. In a letter published in the Technician on April 11, the workers wrote that the Black female workers were being put in positions that could degrade them. Caldwell replied that he had tried to handle the situation compassionately. The following Monday, 16 workers went to Caldwell’s office “to protest the firing of four PP [Physical Plant] maids and demand the removal of all black women from work assignments in male residence halls,” according to the Technician. They were arrested when they would not leave the chancellor’s office.

1911 Building

The 1911 Building was home to the first courses at NC State to offer an African American perspective. “Black Study courses at State will be available for the first time this fall,” an article in a 1969 Technician read. The initial offerings were four courses: English 395 (“Black American Literature”), History 272 (“The Afro-American in America”), Political Science 403 (“Black Americans in American Politics”) and Political Science 404 (“Black Ideology”).

Tompkins Hall

The African American studies minor, introduced in the fall of 1988, was based at Tompkins Hall. Earlier that year, Black students had pushed their concerns over racism and a lack of African American presence on campus with Chancellor Bruce Poulton. “The issues include a lack of black instructors, low graduation statistics for black students, the lack of black coaches and the creation of an African-American studies program,” reported a 1988 issue of the Technician. The new minor was one outcome of that dialogue. “This provides any student with a place to realize the incredible influence and contributions African Americans have made to the world,” Thomas Hammond, then director of African American studies, told the Technician.

West Dunn Building

The building became a new home for the African American Cultural Center in 1974. The renovated print shop was the first space on campus that Black students, who had been meeting in the basement of the YMCA Building, had to call their own. Don Bell, president of the Society of Afro-American Culture, led a movement that spring to secure a space, asking Dean of Student Affairs Banks Talley to consider allowing Black students to meet in the West Dunn Building. After a few weeks of discussions, he and Chancellor Caldwell granted the request. The center is now located in Witherspoon Student Center, named for Augustus “Gus” Witherspoon ’69 MS, ’71 PHD, the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from NC State. He was the first Black person to have a spot on campus named for him at NC State.

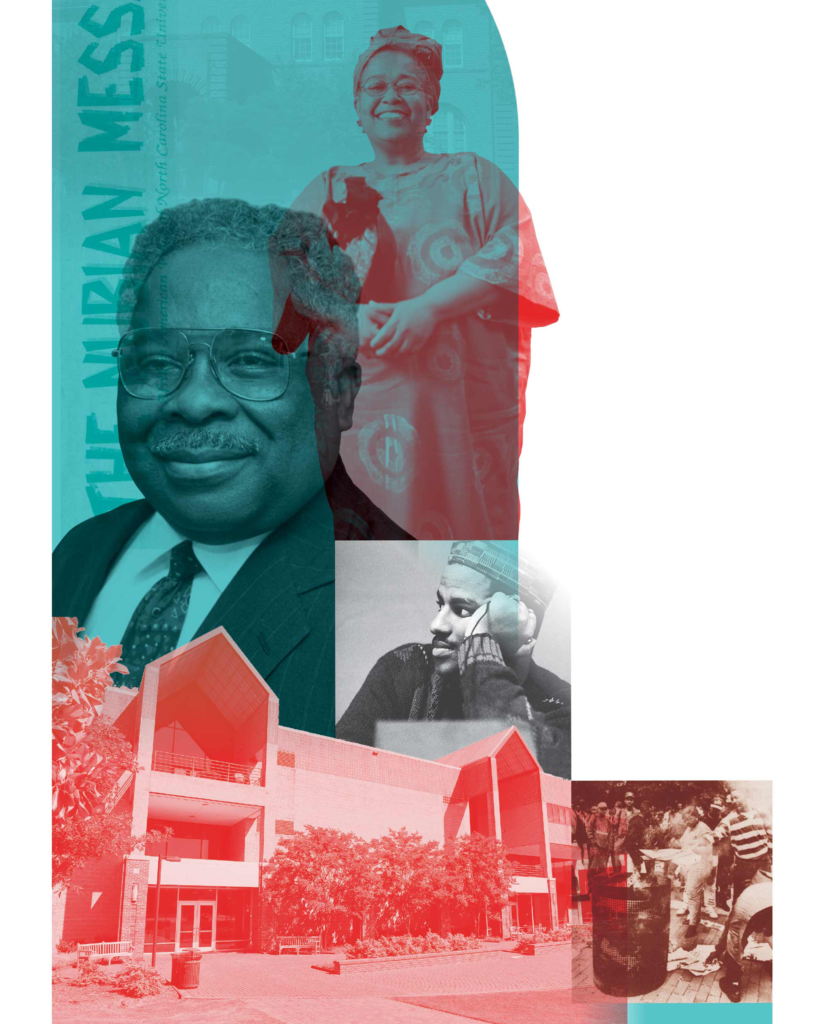

Witherspoon Student Center

The building, home to the African American Cultural Center, is the home of the Nubian Message. In the fall of 1992, Black students held demonstrations over their concerns about a lack of representation, staging a sit-in at WKNC and gathering in the Brickyard to burn copies of the Technician in response to a controversial opinion column that addressed race. “We need a black paper on this campus,” said Greg Washington ’89, ’91 MSE, ’94 PHD then a graduate student who organized the rally. The result was the Nubian Message, published for the first time on Nov. 30, 1992. “At N.C. State, one of our main concerns has been unfair and unjust media coverage of the African-American community on this campus,’’ editor-in-chief Tony Williamson wrote in the first issue. “Rather than sit around and wait for some fair coverage by that other paper on campus, the Nubian Message has been created to represent the African American community at NCSU totally, truthfully, and faithfully.’”

Talley Student Union

In September 2016, Talley Student Union was home to a protest that was part of the Black Lives Matter movement. The protest followed the deaths of Terence Crutcher, a Black motorist shot and killed by police in Tulsa, Okla., and Keith Scott, who was shot and killed by police in Charlotte, N.C., four days later. Three hundred NC State students wore black, and sang in unison and walked to Talley, where they lay down in the atrium, staging a die-in. “We want to take a moment of silence and let the voices of the victims speak loudly,” said Student Body Vice President Brayndon Stafford ’18, according to the Nubian Message.

Hillsborough Street

For much of the 1960s, Black students at NC State could not eat at restaurants on Hillsborough Street. According to an April 29, 1963, Technician article, the first three restaurants to seat Black patrons were Baxley’s Mignon, Baxley’s “Tin Box” and the A&W Root Beer restaurant. The article also reported the Varsity Theater had integrated, but noted that other establishments would recognize only take-out orders from Black patrons. Days later, the Technician reported the S&W Cafeteria and the Sir Walter Raleigh Hotel Coffee Shop denied service to Angie Brooks, assistant secretary of state for Liberia who had spoken at NC State, and her nephew, a student at Shaw University.

Free Expression Tunnel

The Free Expression Tunnel has a storied history at NC State, serving as a place where students and visitors have celebrated wins, promoted various causes and shown off their art. But there’s a painful side to that history, as well, as it’s also been a home for the expression of hate. In 2008, students painted racist messages and threats against then president-elect Barack Obama on the night of his election. Again in 2010, Obama was the subject of a demeaning and racist image. “Some people think this tunnel is necessary, others see it as a tunnel of oppression,” Tracey Ray ’93, ’97 MS ’01 PHD, then director of multicultural student affairs, told the Technician. “We want to foster and nurture innovative thought and growth at NC State, but we also want to foster personal and professional growth. I’m not sure the [F]ree [E]xpression [T]unnel does that.”

Reynolds Coliseum

Barack Obama spoke as president at the Old Barn in September 2011. But decades earlier, Reynolds Coliseum was home to the first Black female basketball players at NC State, part of the varsity team that formed in 1974. That initial squad, coached by Peanut Doak, included two Black players: Gwen Jenkins and Cynthia Steele (now Exum) ’76, whose ball-handling abilities Doak celebrated heading into the team’s first game that season against the Virginia Cavaliers.

Carter-Finley Stadium

On Nov. 7, 1970, Mary Evelyn Porterfield was crowned NC State’s first African American Homecoming queen, or “Miss Wolfpack,” at halftime of the NC State-Virginia football game at Carter-Finley. “I think State is three years behind in the trend,” she told the Technician. “. . . I realize that this is a victory for blacks on campus and particularly for the black female.”

Riddick Hall

NC State integrated in 1953, when two Black graduate students entered the engineering program, housed in Riddick Hall. One of those students, Robert Clemons ’57, is the university’s first Black graduate. Three years after it accepted grad students, NC State admitted the first four African American undergraduate students. They too studied engineering. They were Ed Carson ’62, Manuel Crockett, Walter Holmes ’62 and Irwin Holmes ’60. Walter Holmes went on to be the first Black student to join the marching band at NC State. And Irwin Holmes, in 1958, became the first Black student to join a varsity sports team at the university, playing for the tennis team. Two years later, he would become the first African American to serve as a team captain at NC State and in the ACC. Built in 2007 and dedicated in 2018, Holmes Hall is now his namesake.

This story appears in the winter 2020 issue of NC State magazine. Members receive the award-winning publication in their mailboxes every quarter.