Altered State

A year after COVID-19 began to spread across the nation, we're taking a look back at the two weeks in March that changed everything.

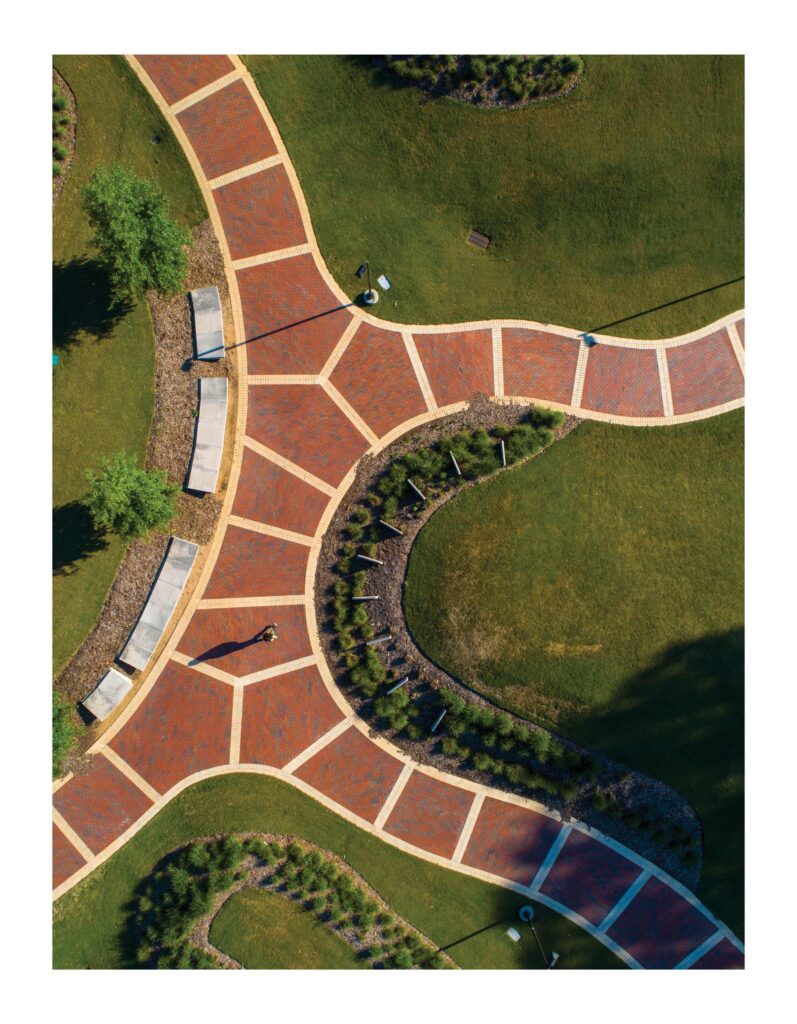

By Sylvia Adcock ’81 | Aerial photographs by John Hansen

Editor’s Note: As we approach a year after the coronavirus spread across the country, we’re taking a look back at the two weeks in March of 2020 that changed everything. This story originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of NC State magazine.

Louis Hunt ’83, ’91 MS, ’00 PhD can remember the day it felt real.

It was the afternoon of March 6, and Hunt, the university registrar, was in the Park Alumni Center for a meeting of NC State’s Board of Visitors. That week, two coronavirus cases had been reported in North Carolina. “The provost and the chancellor pulled me aside,’’ Hunt says. “And they said, ‘What would it be like if we have to extend spring break?’”

Hunt was taken aback. “At first it was like, wow,” he says. “It seemed like a wild idea at first blush. And then you think about it and you realize — we can make it work.”

Making it work ended up being about more than that extension. During two weeks in March, NC State quickly sent students home, scaled down operations and essentially emptied the largest college campus in the state, a place that serves 36,000 students.

Academia is not known for quick turnarounds, and like many universities, NC State is an institution that traditionally acts in measured ways. It was like asking a battleship to turn around in a tight harbor. Beyond the obvious changes — online classes and shuttered dorms — there were behind-the-scenes scrambles, like figuring out if federal financial aid tied to the academic calendar would be affected.

As the virus’ toll began to increase and college students were heading out for spring break, university officials across the country realized the burden would fall on them to keep their campuses and communities safe. “We saw it coming, but it happened very fast,” says

Katharine Stewart, vice provost for faculty affairs. “We didn’t have a lot of time to adapt.”

Stewart had a familiar feeling that first week of spring break. She has a master’s in public health and a Ph.D. in clinical medical psychology and worked in an AIDS clinic in the 1980s.

“Those of us who were working in HIV,” she says, “knew it had the potential to be much bigger.” In March, she says, “I remember thinking, ‘This feels familiar to me.’ This feeling of, this epidemic is bigger than many people think it is.”

Much to Consider

Amy Orders started tracking the coronavirus in December, when it was still mostly confined to the city of Wuhan, China. As NC State’s director of emergency management and mission continuity, she’d helped develop plans across campus for emergencies ranging from hurricanes to active shooters to hazardous materials — and pandemics. By January, Orders and her UNC-system counterparts were talking regularly.

“We started talking about the ‘what if,’ that we were going to have to take that plan from two or three years ago and dust it off,” she says. In February, she started holding meetings with officials from across campus including the provost’s office, University Housing and the Division of Academic and Student Affairs. Her team pulled in experts, including Dr. Julie Casani, director of Student Health Services. As a public health official for the state of Maryland in the early 2000s, Casani oversaw data-driven responses to the first SARS cases.

As spring break approached, Casani laid out a worst-case scenario if the campus continued on a normal schedule. It was grim: The students would return, gathering in dorms and apartments and then heading to class. And then “one or two sick people spread the disease before we were able to control and contain it. We would soon have an entire campus ill or very much at risk — and the entire campus includes not only students but faculty and staff. The highest risk individuals were probably faculty and staff, and that was part of the equation.”

You feel such a weird responsibility to ensure whatever decision we land. on is the best it could be in the worst possible scenario.

— Donna McGalliard ’92

Director, University Housing

From his office, Hunt and his team began to look at the implications of extending spring break. Federal financial aid and housing allowances are tied to specific dates in the semester. Would a spring break extension affect that? Then there was the university’s accreditation with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. “Would we have delivered the right amount of instruction for the credit hours?” Hunt says. Veterans’ benefits for students could also be affected by the semester’s calendar.

On the last day of classes before spring break, Wake County had just reported its first case of COVID-19. The term “social distancing” was not yet a part of the public conversation. The students who lined up at Starbucks in the Talley Student Union before heading to class didn’t know it would be the last time that spring they’d see their professors in person or their classmates face-to-face.

In the provost’s office, Stewart and partners across the university had already been working on “academic continuity” planning. For two years, her office had been meeting with the registrar’s office, the libraries and the Office of Information Technology to develop a plan for times when, for any reason, classes couldn’t meet on campus or were disrupted. DELTA, the unit that helps faculty put coursework online, worked with the provost’s office to launch a “Keep Teaching” website. It featured tips for communicating with students online, a tutorial on how to move a course online quickly and other resources for professors not accustomed to virtual learning.

The provost’s office sent a memo on March 6 directing every instructor to create a plan to move classes online. “By the time we were writing that memo,” Stewart says, “we really saw the wave coming and realized that to keep our campus safe, we were going to have enact some very big changes very quickly.”

Should They Stay or Should They Go

Kim Priebe is used to putting out fires. As director of NC State’s Study Abroad programs, she starts every day with a comprehensive briefing of health and security information from around the world. Civil unrest in a small African country may not make the evening news, but Priebe will know about it — and how to keep an eye on any students there. Her team began tracking students in Asia when the outbreak first began. “Then we realized, this is not regional,” Priebe says.

By early March, Italy was a hot spot of infections, and NC State had 56 students spread out across the country. Programs were suspended and students were advised to return home and self-quarantine for two weeks. A handful of students who were not able to quarantine at home were put up in apartment-style rooms in a dorm that was under renovation. They were supplied with thermometers and University Dining delivered meals, including weekend care packages that sometimes included fresh-baked cookies from Yates Mill Bakery.

It’s a weird experience. It’s kind of like a ghost town.

—Elizabeth James

Director, International Services

Several hundred students were still overseas in places like Iceland, Australia and Denmark when it became clear that every program would have to be suspended. “It was difficult news to have to share,” Priebe says. “When your profession, your life, is all about creating programs so that students can have this transformative experience abroad. And instead you’re ruining dreams, dismantling the programs you’ve worked on, that the students have saved for and mapped their entire degree program around. I don’t even have a word for it.”

The War Room

The conference room in Pullen Hall had become what Donna McGalliard ’92, assistant vice chancellor and executive director of University Housing, called her “war room.” Fueled by bags of mini Reese’s Cups and cans of mixed nuts, her team had been holing up to play out scenarios. Among them was a shutdown of residence halls. She discussed the possibilities with colleagues in the UNC System. “It was intense,” McGalliard says. “I had to get up and walk away at one point. You feel such a responsibility to ensure whatever decision we land on is the best it could be in the worst possible scenarios.”

On March 11, a few days after spring break began, Chancellor Randy Woodson issued a memo to students, faculty and staff: Spring break would be extended by a week. Most classes would go online. And students were discouraged from coming to campus. A week later, on March 17, McGalliard was called to an early morning meeting. Under advice of the UNC System, NC State would be announcing that students should remain off campus and return to their permanent homes after the break if possible. Her team needed to prepare to close the dorms and provide a draft message to students by 10 a.m. — it was already 8:45 a.m. She was able to lift language from an email that had already been prepared in the war room.

At the time, few states had imposed stay-at-home orders, and for some, the actions of the university along with others around the country were a sentinel event. Stewart, the vice provost, recalled that Magic Johnson’s announcement that he was HIV positive changed the conversation about HIV. “It just shifted in that moment,” she says. “And for some people, ‘Oh, we’re not going to be allowed to come back to campus,’ or ‘My child is not going to come back to campus’ — there was this realization that this is a real threat.”

On March 22, the two-week spring break ended. It was the students’ final day to come back to campus to get their belongings. Those who could check out of their dorms were allowed express check-out, meaning they could leave their key in the room in an envelope supplied by University Housing. McGalliard’s staff, joined by parking and transportation staffers, had taped envelopes onto each dorm room door — that’s 4,000 in all. “We covered millions of square feet in three hours,” she says.

Move-out days on a college campus are traditionally filled with good-bye hugs and laughter as students head out on a summer adventure. This one was different. McGalliard took her dogs and family to campus that last day. “You could see the disappointment in the students’ faces as they were taking their items out to their cars. It’s not supposed to be like that, right? It was almost somber. It was eerily quiet,” she says.

As she told the students she was sorry to see them go, she says, “everyone had the same sense: It’s not what we want to do, but we know it’s what we need to do.”

This story appears in the summer 2020 issue of NC State magazine. Members receive the award-winning publication in their mailboxes every quarter.