A Hole New World

Stacey Moore '91 has built an empire with his American Cornhole League on bean bags, boards and his belief that anyone can win.

Written by Chris Saunders | Photography by Susan stocker

Fort Lauderdale, Fla. — It’s a sunny South Florida morning in late January, a month and a half before the coronavirus will change the world and just two days before the Super Bowl in Miami, Fla.

But this morning, about 30 miles north of Miami, the Broward County Convention Center is set up for a different sport, one that features bags more than brawn. Rows of wooden boards, each with a hole nine inches below its top edge, sit ready to help crown champions from a field of 600 competitors. This is the 2020 American Cornhole League (ACL) Kickoff Battle. Players from New Orleans, La., huddle up and listen to strategies put forth by “Billy Bean Bags”— that’s the name on the back of his jersey (yes, jersey). Across the expansive setting, pro Frank Modlin signs an autograph as another board big-timer, Adam Hissner, walks through the crowd carrying two Bud Light bottles. “This,” he says, “is how you’re supposed to walk around at a cornhole tournament.”

The event is one gigantic tailgate featuring a game most of us know only through backyard get-togethers. Cornhole is a simple game: You toss a 6″-by-6″ bean bag through the air and either land it on the board or get it in the hole to score points, with the first to 21 the winner. But what’s unfolding in the Broward County Convention Center is more organized and more intense than your average backyard game over a few (who are we kidding?. . . many) beers. This is the world of the American Cornhole League and its creator, Stacey Moore ’91.

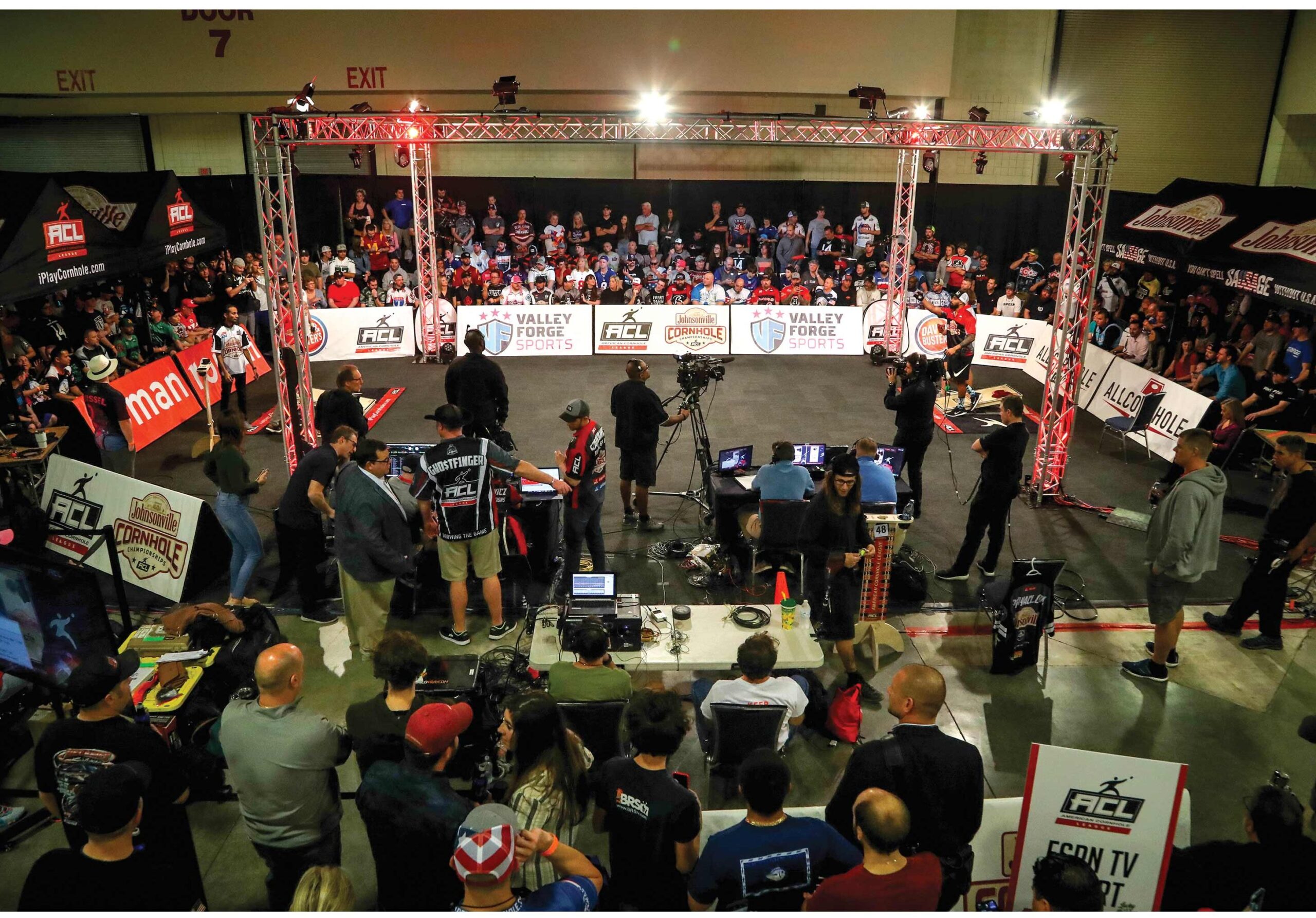

Moore is also the commissioner of the ACL, which he formed in 2015. You’ll find him at an informal command center on an ESPN set, wearing an ACL jersey and athletic pants. Even on his radio spots and on TV, he comes across as more of a fishing buddy than an in-your-face promoter. But his methods have worked despite his lack of bravado. Since 2015, he’s become the cornhole king, brokering two television deals with ESPN to make the game appointment television on a national network, securing lucrative sponsorships with Johnsonville, the sausage company, and other businesses, and introducing purses in the tens of thousands of dollars at ACL’s national tournaments, where a champion can leave a couple thousand dollars richer (although that usually goes toward covering travel).

“He didn’t start [cornhole]. We get that,” says J. Scott Collins, a 40-year-old pro player from Bristol, Pa. “But he’s growing it.”

Moore’s road to ruling the cornhole world is as circuitous as the game is simple. He’s had a few speed bumps, from initial doubts of players to the difficulty of rounding up sponsors. “Several times along the way, I felt like I failed, and I’ve taken it very hard during a lot of different points in this journey,” says Moore, whose voice is always quiet. “You have those days where you’re like, ‘Man, I’m just beating my head against the wall. I need to just give up.’

“But then you find something. Something happens. Or you find something deep inside of you and you’re like, ‘Yeah, you can’t give up. You need to just keep on going.’”

Moore, 50, grew up in ACC country — Charlotte, N.C., to be exact — which helped him formulate the dream to grow up and work in a sport (just one with more round equipment than square). “I grew up going to ACC tournaments with my dad and grandfather, which was really cool to be able to experience back when the ACC was eight teams,” he says. “When the Hornets first came to Charlotte, we were season ticket holders from Day One.” He graduated NC State as a business management and economics double-major and joined up in the early 1990s with his father, William Stacey Moore ’67, and grandfather, Joseph Moore ’36, in their venture, a new minor-league basketball team. Moore was director of merchandising and purchasing for the Greensboro City Gaters of the Global Basketball Association, coached by former Wolfpack assistant Ed McLean. “I got to pick out the uniforms and that sort of thing,’’ Moore says, “and they said we had the best-looking uniforms in the league.”

Moore thought he’d be a basketball lifer, but the Gaters folded after one season. That experience nonetheless introduced him to the world of running a league, whether it was the meetings his father included him in or watching the behind-the-scenes politics. His reliance on the lessons he learned in Greensboro is on display in Fort Lauderdale on the opening morning of the ACL Kickoff Battle under the red and white lights — he slyly grins when asked if he chooses the colors — and scaffolding of the ESPN set. It’s on this set that the tourney’s biggest matches will unfold, be taped and filmed live for network play over the weekend. And it’s there that Moore fulfills all the roles of commissioner, searching for the correct banner to feature one of his sponsors, like Johnsonville. He fields compliments from competitors with teams such as the Mother Shuckers, Motor City Cornhole and the Alleghany Mountain Baggers from Virginia. And he lends an ear when an ACL superstar approaches him with a concern.

After the GBA gig ended, Moore began a 25-year journey that has culminated in the role as a cornhole commish. He got an MBA from the University of South Carolina, worked in finance and even considered becoming an agent for pro players. But in the late 2000s, the entrepreneur’s itch got him.

It was an itch he scratched with an old pastime. Moore and his father had been going to Wolfpack football games since at least 1979, when Moore recalls tagging along for his first game at Carter-Finley Stadium, a Wolfpack loss to Penn State (Moore still remembers his teary-eyed ride home). Fast-forward some 30 years and Moore looked around on a game day and found himself in awe of how far tailgating had come. Gargantuan RVs. Elaborate buffets of Golden Corralian proportions. And spirited contests like cornhole. “I was just looking around and seeing all the money that was being spent on tailgating, and I said, ‘There’s got to be something here.’” So he created Tailgating Ventures, what he calls a “tailgating incubator,” creating brands tied to having fun in a parking lot before a game.

One of those brands was the American Tailgating League, which hosted tourneys featuring games you might see on a beach, like ladder golf and cornhole. Moore took it national in 2011 in Las Vegas, Nev., for an event called MegaGate. “A tailgating Olympics,” he says. But the event was more flop than mega. And a second MegaGate merely broke even. But Moore was encouraged.

“Man, these cornhole people are just different,” he says. “Why people are playing cornhole more seriously than other sports, I didn’t really get it. . . . I wanted to have a beer in my hand and just throw back and try to hit the board. That was my strategy. . . . Then I was watching these players play and hearing their passion and hearing them complaining and seeing the intensity that they had.”

The cornhole empire of Stacey Moore ’91 includes a digital platform and a broadcasting contract with ESPN. The network’s main stage serves as the perch from which Moore takes in the board atmosphere, from players competing just for fun to pros building a brand for themselves and playing at the highest level for championships.

That intensity is apparent on the first day of the Kickoff Battle in Fort Lauderdale, when pro Blake Demale is challenged by another opponent on a rule violation. Essentially, one foot must always be within three feet of the board, and Demale’s opponent says he overstepped his bounds. They use a tape measure and find that the wayward step was within the rules. “A total mind game,” Demale says.

ACL players travel from all over the country. Demale comes from San Francisco, Calif. A mother from Texas says she paid $800 to fly her daughter and a friend to the events, just to see her daughter finish fifth in her Friday morning bracket. Cleveland, Ohio, is represented. Washington, D.C. And Florida, seemingly a hotbed of cornhole craze. The players include all genders, ages, races and skill levels, with the top players wearing sponsor names on their jerseys, which designate them as pros. At any given national event, about 75 percent that show up are pros.

Ryan Smith, 29, is one of the only pros who wears a glove on his tossing hand (to keep down the sweat, which can interfere with the bag’s release). Outside Exhibit Hall D, a fan asks to have his picture taken with Smith, who poses and smiles. “I took a number of pictures today,” says Smith, who played defensive back for three years at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va. “It brings me back to that,” he says. “People know me.”

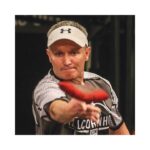

By day, Smith is a project supervisor at a D.C. logistics firm. Like him, all the pros have day jobs. Christine Papcke, a top women’s competitor, worked 23 years for Nationwide Insurance before taking a job in computers for the bean-bag company Reynolds Bags. Samantha Finley, a 28-year old pro from Clermont, Fla., is a patient-care coordinator for a hearing-aid company. And Frank Modlin is a 51-year old middle-school physical education teacher in Williamston, N.C., who has made cornhole a part of his classes. “The only boards I have at school are the ones I carry and leave at my office,” he says. “So I break them out every now and then, and the kids want to challenge me.” Modlin is also a star because of the Game Changer, a bag he invented and patented. (The patent office in Washington, D.C., is no joke, he says.)

Ear buds are omnipresent at the Kickoff Battle. The cocktail of gravity and players’ arm strength results in a rhythmic and relentless thwacking of bags to boards that starts at sunrise and continues amid the round-the-clock side games that go to midnight. But the players sport ear buds so they can listen to music during matches — from Rage Against the Machine and Soundgarden to country rap artists like Colt Ford. Despite their different musical tastes, all the pros have the same basic story. They first played cornhole in a backyard or at a college party. They used YouTube to learn such shots as the “airmail,” a high-arcing toss that moonshots through the air and touches nothing on its way through the hole. They started going to events in their hometowns called “weeklies.” They won, started going to regional events, lost — often by a lot — but got better. And eventually they played so much, they qualified for the ACL recognition as a pro by finishing high enough in the standings either in a conference or the entire ACL. They still play in local events as well as the three national tourneys Moore puts on every year. They’ll drop $1,000 to $1,500 on travel just for the weekend. And that is about as much as they can make if they win their draw.

Companies offer sponsorships to help the pros cover travel expenses. Moore helps broker the deals, which also help pay for the players’ equipment — their bags. Pros are not superstitious about their bags, by the way. They don’t care if you touch them or even play a game with them. But travel can be dicey. “I’ve learned, traveling through the airports, you’re better off to just go ahead and tell the TSA guys, ‘Hey, look, you know, I’ve got some crazy things in here. You know, it’s cornhole bags,’” says Modlin. “They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, cornhole.’”

Moore says the best thing he’s done for the league was creating the ‘bring your own bags’ policy as opposed to restricting players to any one brand. Yes, deregulation happens in cornhole, too. “I think we had over 30 different manufacturers that submitted bags for approval,” he says. “We’ve created a lot of small businesses out of this rule, and it’s sparked innovation in the game.”

But Moore’s true gift to the ACL and its players is his efforts to legitimize the sport. He says that when he initially wanted to start the league, cornhole players and other tournament organizers viewed him as a bit of an outsider. Some doubted he could pull it off. Getting sponsors for the league helped. He got Johnsonville after contacting a representative at the company through LinkedIn. Others followed, like Subway and All Cornhole out of Utah. Moore says he knew early on that the key to securing the top players was to commit to paying out prize money. ACL national events promise $10,000 to $50,000 purses spread out among the winners. He’s also enticed celebrities to make appearances at ACL events, like New York Giants quarterback Daniel Jones and New York Jets quarterback Sam Darnold. They face off with ACL pros in a recorded event for ESPN called Super Hole. (And yes, their match begins with a coin toss with the winner choosing which side of the board they’ll throw from during the match.)

Before that match is filmed for television, Moore leaves his perch on the ESPN set and heads over to a behemoth bus/RV sporting the logos of the ACL and some of its sponsors. He disappears inside to change into a dress shirt and pants and a sports jacket to film an interview. Moore says he’s had to adjust to channeling his inner P.T. Barnum. “I was never a seller,” he says. “When I created the American Cornhole League, I had to become more of a seller.”

Though he’s not always comfortable in these spots, they’ve worked. Nothing is more indicative of that than the deal with ESPN, which Moore cultivated in 2016. Those were rough waters to navigate at first, since he’d never negotiated a television deal. He still remembers the first national telecast, beamed out to the nation on ESPN2. About halfway through, the executive producer came out of the truck and asked Moore if he knew what was going on. “He said, ‘You’ve gone viral on Twitter.’ And he’s like, ‘Everyone up in Bristol [where ESPN is based] is just laughing like crazy about how well this is going,’” Moore says. “Immediately, they agreed to a three-year deal with us right out of that broadcast.”

The ACL and ESPN re-upped for another three years in January 2020.

The Pros Say So

American Cornhole League pros offer their thoughts on what separates players in the backyard from the big time.

Here are their tips on what makes a good cornhole player:

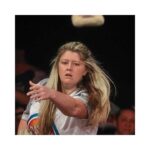

| Frank Modlin, 2019 ACL Devour Pizza Man of the Year runner-up: They definitely have to be a well-rounded person. You have to be in control of your emotions. That’s in any sport. And then, of course, you’ve got to have skill sets. If you are a diverse player, where you have multiple threats, if you can throw the block shot, if you can throw the push shot, if you can throw the airmail shot, and feel comfortable with them. That’s what makes a really good player. | Christine Papcke 2020 ACL Kickoff Battle women’s doubles champion: You have to deal with a crowd of people, that’s for sure. And you’ve got to stay calm and focused, but you also have to play your game. . . . When I play, I step up. I just take a deep breath and make sure I plant my foot. I follow through. You just learn to have things that you say, back and forth in your head. Sometimes they come out loud. |

| Samantha Finley, ACL 2019 world champion in women’s doubles: A lot of times, I find I just play better against better people. You definitely realize, “Oh, I’m not the only one who’s good at this game.” | Ryan Smith, an ACL top-10 singles and doubles player: In football, we used to do mental imagery, where you just envision plays. At big events, you just visualize what you need to do. Hitting an airmail. So that definitely carries over. |

Part of what makes Moore’s legitimizing the sport easy is the egalitarian appeal. The ACL’s motto is, “Anyone can play. Anyone can win.”

That’s why the sport is growing, says player Ryan Smith. “You’ve got these guys that throw locally, that don’t travel but watch this on ESPN. They’re like, ‘I can compete with these guys.’ Then they start playing and playing and say, ‘I’m going to do it this year.’”

Trey Ryder, a 26-year old chemical engineer who’s the voice of ACL’s ESPN telecasts, says that when marketing the ACL, Moore focuses on the everyman and doesn’t try to make icons out of their pros. “We want other people to beat them and get good enough,” Ryder says. “There’s an element to cornhole that literally, no matter your demographic, your skill, your background, your race, your gender, you can compete and you can play this game.”

That feel has certainly been in the ACL air much of 2020 as the sports world has been devoid of action because of COVID-19. Moore has made sure the league’s Twitter feed is alive with posted shots by fans around the country. (Hello, Trickshot Tuesday!) While the rest of us tried to adjust to life on Zoom, the league went one step further, launching the ACL Virtual app that lets players have virtual matches apart from each other. And what was the competition that beat the PGA, NBA, NHL and MLB in safely coming back? None other than the ACL, which has held events that aired for seven straight weeks on ESPN amid COVID-19 in 2020, with masks becoming just as much a fixture of the game as a player’s bags.

But what better way to spread that message than to take ACL’s bags and boards to the one place where amateurs can compete internationally? The next step to cornhole’s legitimacy? Think a flame. Think five interlocking rings. (Or five squares?)

“I just happened to push the right buttons at the right time for it to go the right way so far,” Moore says. “I think you’ve got to chuckle at it. . . . Certainly, there was enough people telling me that this would never be a sport, that I do chuckle that I have been able to legitimize it as a sport.

“The next stop is the Olympics. That’s the goal.”

This story appears in the fall 2020 issue of NC State magazine. Members receive the award-winning publication in their mailboxes every quarter.