When State Got Sick: Revisiting The Flu of 1918

The influenza pandemic of 1918 swept across the world — and NC State’s campus. The college answered the call and instituted changes that helped guard against such a spread again.

I wrote this story during the summer of 2018, and NC State magazine ran a version of it that fall, marking 100 years since the 1918 flu pandemic. I remember leaving work on an early July evening after wrapping up a round of edits from my colleagues on the story. My wife picked me up, and we hopped on 40 East to see the Carolina Mudcats. I remember the cap I bought, blue and yellow as a nod to the team’s Major League affiliate, the Milwaukee Brewers. And I remember laughing with my wife after the game as stadium fireworks danced and crackled above us.

It seems like for much of 2020, all I’ve done is remember. It seems like forever since the last time I was on campus — the eve of the ACC men’s basketball tournament in early March. Laughs with all my friends and colleagues at our Park Alumni Center office feel farther away than the 19 weeks it’s been.

When I wrote this story two years ago, I never imagined we would once again be facing a global pandemic here in Raleigh on NC State’s campus. But the story of the 1918 flu at State College feels very close, so close, in fact, we thought it was worth revisiting. Much of what I found in my research seems to match our present reality. The rapid spread across the country of an uncontrollable pathogen. An institution’s mission put on hold. College students’ lives disrupted. And most importantly, NC State going to work to help where it could.

— Chris Saunders, July 2020

The U.S. was in its second year of fighting World War I in the autumn of 1918, and the campus of the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering turned its focus to war and military training. With the establishment of the Student Army Training Corps, the majority of the all-male student body no longer wore suits and ties to class, instead donning uniforms and brimmed hats. The exhibition grounds across Hillsborough Street were transformed into Camp Polk, with British Mark V tanks replacing fair and farm animal exhibitions. It was the only spot in the country designated as a training space for the new land ships and the warfare that would accompany them.

The war should have been enough for State College to endure in 1918.

But as the war entered its waning months, the country faced a different attack at home. It didn’t wear a uniform. The weaponry it carried could be seen only with the help of a microscope. And unlike the fight against Germans abroad, the U.S. had no answer to combat its foe. State College, along with the nation, was caught in the crosshairs of Spanish influenza.

Since opening its doors in 1889, the college had grown from Main Building (now Holladay Hall) into a campus of seven academic buildings, a library and armory, a dining hall, a power plant, some farm buildings and seven dorms. The two largest dorms — the 1911 Building and Watauga — together held around 360 students in close quarters with shared bathrooms. The conditions were ideal for an unusually virulent influenza strain — in fact, it was the same H1 N1 strain that caused panic in the U.S. in 2009 — to spread across NC State’s campus, carrying the infirmary past its capacity, killing off students (and alumni) and canceling football games on campus and fairs around the state. In a single month — October 1918 — the flu infected nearly half of the student body and killed 13 students. That included more deaths in a two-week span than had occurred at the college in the first 30 years of its existence.

Here are some of the stories of how State College fought fevers and battled back.

Contagion On Campus

The Spanish flu of 1918 infected 500 million people and killed 50 million worldwide. There were 675,000 U.S. deaths, with almost 200,000 in October. In North Carolina, more than 13,000 died.

When the influenza epidemic first brought its deadly touch to State College’s campus in fall 1918, school had only been in session for about two weeks. The two stories of the college’s infirmary — now part of Winslow Hall — held wards for patients. There was one physician and one matron-nurse.

It took only one day for the flu to overwhelm the staff. “[S]o rapid was the spread of the epidemic that in less than twenty-four hours the College Hospital was overcrowded with victims of the disease,” reported the Nov. 1, 1918, issue of Alumni News. The Y.M.C.A. building was filled with cots and turned into a hospital, welcoming the overflow of patients. Other patients were taken to Rex Hospital. Some died.

We could hardly have expected that the work of the students would be up to the usual standard during the fall term

— Wallace Carl Riddick

When outlining its effects on campus in his annual report to the Board of Trustees in May 1919, college president Wallace Carl Riddick cited the “almost certain contagion” as the reason his administration and faculty had lowered expectations of student performance the previous fall. “[W]e could hardly have expected that the work of the students would be up to the usual standard during the fall term,” Riddick wrote. But that didn’t mean they didn’t perform in other ways. With the infirmary staff strapped, students jumped in and worked wherever they were needed. They nursed in the infirmary. They cooked in kitchens and cleaned, filling the roles of janitors.

Riddick’s excuse about academics is a pretty good one. Consider this. There were only 1,017 students then, and nearly half — 450 — got the flu. In 1918, there was no shot to offer protection. Individuals contracted infections like pneumonia on the heels of the flu, and they had no antibiotics for a remedy. There was little public health infrastructure in North Carolina cities and counties to focus in some centralized way in battling the spread. Warnings did appear in papers advising people to buy Vicks VapoRub (then based in Greensboro, N.C.), shy away from spit, wash hands and put Vaseline in noses. An Oct. 26, 1918, issue of Extension Farm-News warned against shopping in person and sharing items such as drinking cups, silverware, cigar-cutters and toothpicks, along with one other big no-no. “Avoid kissing, especially on the lips.”

Now and Again

Almost no one thought we would see NC State’s campus face another global pandemic like the influenza it staved off in 1918. Then came 2020. Here’s a comparison of the 1918 flu to the coronavirus of 2020 and their effects on NC State.

| 1918 | 2020 |

|---|---|

| The influenza outbreak of 1918 became known as the Spanish flu, but it had little to do with Spain. The name originated because Spain reported its cases more accurately than other countries. Because of World War I, wartime censors did not allow reporting of the sickness in other parts of Europe. But Spain was neutral, so those cases were reported. | In the 2020 outbreak’s early days, some referred to the novel coronavirus as the “Chinese” flu. But many avoided associating the coronavirus with China or Wuhan, the city that was the origin of the outbreak. The World Health Organization cautions against naming a newly discovered sickness after a region. COVID-19, the Center for Disease Control’s official name for the sickness, gets its name from: “corona” (CO), “virus” (VI), “disease” (D) and 2019, the year it was discovered (19). |

| Life on campus bounced back quickly after the 1918 outbreak subsided as students returned for the spring semester. | After spring break, students at NC State finished their 2020 spring semester with online classes and a “Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory” grading option. Summer classes continued online as the university prepared to reopen for the fall. |

| State College’s enrollment in 1918 was 1,017. Almost half the student body got sick from influenza. | Today, enrollment sits right at 36,000 undergraduate and graduate students. As of April 2020, there had been no cases identified on campus. |

| Football season was cut short. “Fifty men reported for practice the first day, but since that time the squad has dwindled, until now we feel lucky if we have eleven men on the field each afternoon,” Tal Stafford ’12, the head coach of the State College football team, wrote in the Oct. 1, 1918, issue of Alumni News. The team’s season, which usually ran eight or nine games in those years, was cut short that season, with the pandemic allowing for only four games in 1918. | This spring, Wolfpack teams were ready for postseason play, but the NCAA canceled all remaining winter and spring championships for 2020, ending all spring sports for the year. It was the first time such a decision has been made by the NCAA. |

| Outside of newspapers — the first Technician didn’t appear until the year after the flu hit — NC State College of Agriculture and Engineering President Wallace Carl Riddick didn’t have an easy way to get updates to students, professors and families. | Chancellor Randy Woodson has used email and a series of video messages to update the university community on how NC State is responding to the pandemic. |

| There was no vaccine for the Spanish flu in 1918. There also were no antibiotics to fight the secondary infections, like pneumonia, associated with it. | Though there are ongoing clinical trials, there are no vaccines or medicines to fight off coronavirus in 2020. We do have antibiotics for secondary infections. |

An Early Grave

Alumni didn’t escape the wrath of the 1918 flu. In fact, eight are among the 35 names listed in the Bell Tower, which commemorates alumni who died in World War I. They are George Hardesty ’07, John Griffith ’14, Robert Waitt ’06, James Scott ’14, John Jackson ’17, Alexander Holladay Pickell ’12, Grover Jordan ’13 and James Thaddeus Weatherly ’18, all of whom died from influenza complications rather than German artillery.

There were 13 State College students who died, and they are memorialized in a list that includes only their names and hometowns on a plain white page in the 1919 Agromeck. Nine were freshmen, two were juniors and two were at State College for one-year programs. Alexander Gibson, a mechanical arts major from Laurel Hill, N.C., died in the Y.M.C.A. building of pneumonia. Henry LaVerne Cox, who came to State College from Siloam, N.C., also died of pneumonia. Edwin Sternberger, who was from Wilmington, N.C., died from influenza after helping nurse sick students.

The Spanish flu also claimed the lives of two women who worked on campus tending to the sick. Lucy Page was a nurse who died from the sickness. Eliza Riddick worked during the day in a State College office and volunteered at night as a nurse. An obituary reports that she went to bed one night and by morning, pneumonia had come on. She was dead within a week. (Her brother, William C. Riddick, died the same way a week before her death.) Riddick, who was the niece of Wallace Carl Riddick, is remembered with a star beside her name noting her death on a bronze plaque that pays tribute to the women who worked and volunteered at the college during the flu outbreak that fall (the plaque now resides in University Archives). Included in the 70 names are wives and daughters of faculty and staff who put their own lives at risk to heal the State College sick. A water fountain honoring the volunteers was on the grounds of the old Wake County Courthouse, but was removed when the courthouse was demolished in 1967.

Riddick’s family in Raleigh received notes from France after her death expressing condolences from soldiers who knew her from their days at State College, all reinforcing the belief, “There never lived a sweeter, gentler or stronger woman than she, in the dawn of her womanhood, had shown herself to be,” according to The News & Observer.

Serving The Sick

As State College worked on healing itself during the flu of 1918, agents from N.C. Agriculture Extension Service, housed at the college, traveled throughout the state to lend a helping hand.

Male agents continued to provide help and direction to rural farmers as had always been their mission. But female agents took on new roles. Not technically trained as nurses, they drove around in North Carolina’s counties with signs attached to their cars reading, “Influenza Relief Workers.” They helped set up makeshift hospitals in elementary schools. To combat food shortages, they led a food conservation program that worked to save wheat flour, meat and sugar. They accompanied doctors into the homes of African-Americans, who felt the burdens of poverty and health care disparity in early 20th century America. (Extension efforts were largely segregated at the time, so that effort included both white and African-American agents.) Women opened and ran soup kitchens, including one in Asheville, N.C., that operated day and night and served as many as 300 people a day. In Durham, N.C., they placed soup recipes and information about influenza in mailboxes. And they offered in-home demonstrations to instruct people on proper sanitation and nursing.

The epidemic interrupted other extension efforts. Schools closed around the state, stalling the recruitment in girls’ and boys’ clubs, forerunners to the 4-H. There had been 250 fairs planned before the flu hit, and most were canceled, along with the N.C. State Fair. “No general State prizes have been offered in the Pig Club work this year,” reported the 1918 annual extension report.

Extension agents placed a newfound emphasis on hot lunches at schools. The idea began in the months following the epidemic. “Mrs. Jane S. McKimmon, Chief of the Division of Home Demonstration Work, suggests that if the children, especially those who have suffered from influenza and have not yet been returned to normal health, could be supplied with a cup of hot milk, cocoa, or a bowl of hot soup, in addition to their cold lunch, better progress in the general efficiency of the pupil would be noted,” reported the Nov. 16, 1918, issue of Extension Farm-News.

The idea behind the program was that children’s mothers would send vegetables from their gardens and other food to school where the teachers would then prepare a lunch. It also guaranteed that at least one day of the week, students would get a hot meal. Meals suggested by McKimmon, who was a 1927 graduate and would go on to serve as assistant director of the N.C. Agricultural Extension Service, included cheese sandwiches, an orange and dates filled with nuts; hard-boiled eggs, biscuits and celery; and baked bean and lettuce sandwiches and apple-sauce. County extension agents implemented the program in at least 40 rural schools in the first year following the outbreak.

That Punk Disease

The closing pages of the 1919 Agromeck featured a poem written by a funnyman who was known across America. Below the title “Walt Mason on the Flu,” two columns detail in rhyme Mason’s attempt at comedic inoculation. “Influenza, labeled Spanish, came and beat me to my knees; seven doctors couldn’t banish from my form that punk disease,” Mason wrote. “I am burning, I am freezing, in my little truckle bed; I am cussing, I am sneezing, with a poultice on my head.”

It’s hard to imagine Riddick seeing much humor in the poem. After all, he’d seen some of his students and both UNC-Chapel Hill’s president and the following acting president die of the influenza that fall and winter. But Riddick sounded hopeful in his annual report to the trustees May 27, 1919. He was pleased with the steady enrollment for the January 1919 term and pointed out that many students who had left due to military service had come back. He voiced excitement at a renewed interest in sports. And he celebrated the health of the student body since January, pointing out that there had been only one severe bout of pneumonia in a student, who recovered.

None of those hopes, however, could blunt the force of how he chose to frame the fall of 1918 as he opened the report: “I submit herewith my annual report as President of the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering, for the session 1918–19, which I feel sure has been the busiest, most strenuous, and in many respects the most trying year in the history of the college.”

That was, of course, until the coronavirus pandemic of 2020.

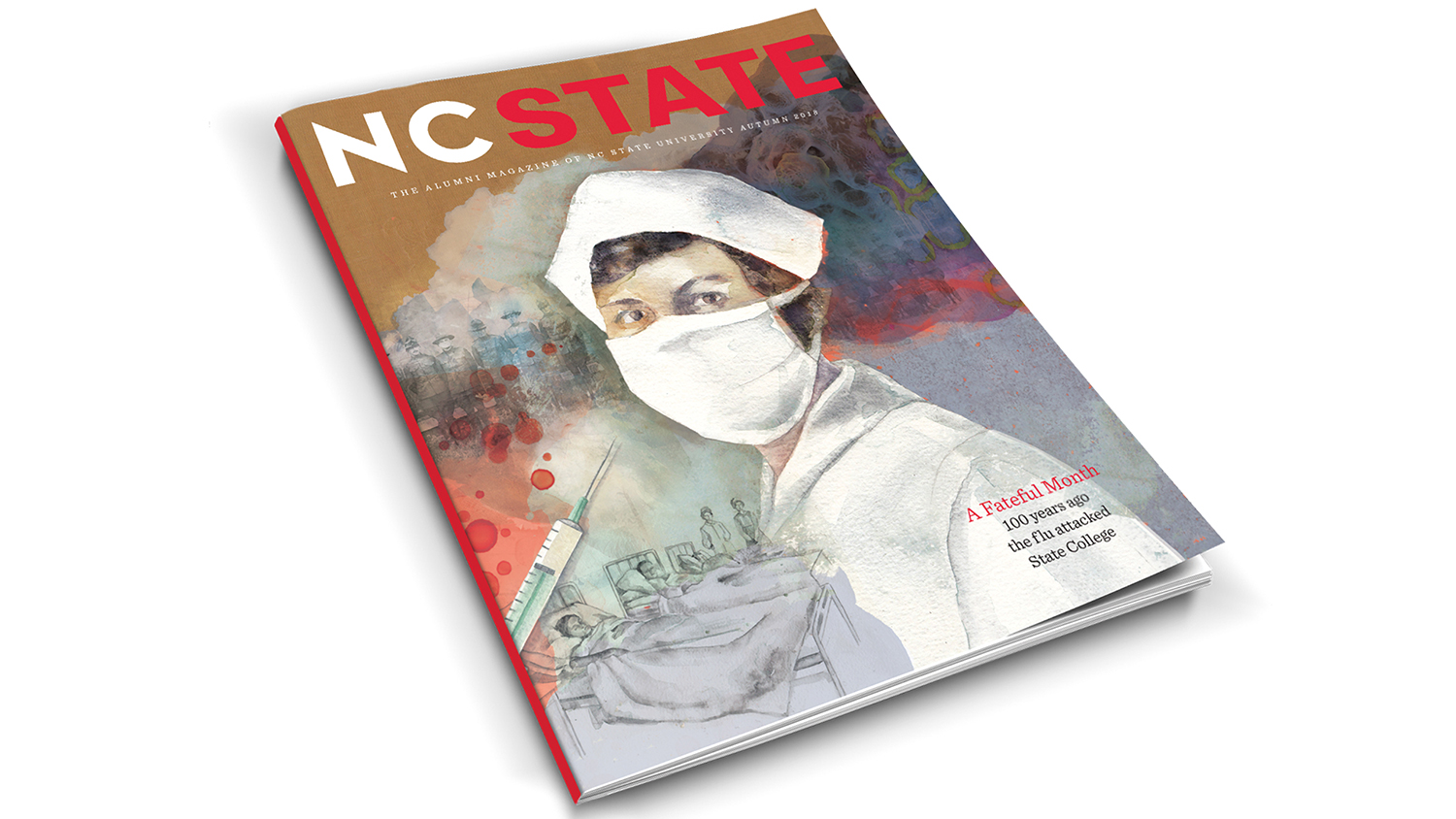

The updated version of this story appears in the summer 2020 issue of NC State magazine. Read the original version in the fall 2018 issue of NC State magazine. Members receive the award-winning publication in their mailboxes every quarter.

Editor’s note: The author used sources including alumni records, the Agromeck, newspaper articles and issues of Alumni News. Todd Kosmerick, the university archivist, and Jennifer Baker, former university library technician, identified sources for a blog series they did on campus life during World War I and a graduate-level public history class that researched the flu pandemic of 1918. Those sources included Board of Trustees records, chancellor’s office annual reports, cooperative extension service annual reports, issues of Extension Farm-News and Jane McKimmon’s book, When We’re Green We Grow. That class’ virtual exhibit, “Soldiering On: The 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic at NC State College,” also proved invaluable.