The 50-Year Evolution of NC State’s Student Center

It was an ugly duckling that became a swan, a ragged maid that became Cinderella, a bland bowl of midcentury modern mush that has become a lively, spicy feast for NC State’s 37,000 students and the 20,000 visitors from inside and outside the university who pass through its doors every day.

When the University Student Center opened 50 years ago this summer, it was hardly the sparkling edifice now known as Talley Student Union. Few wide-open spaces for students to sit and study. No national chain food service. No flying bridge to the future.

It provided, however, much-needed gathering spaces for a work-a-day student community of mostly agricultural, engineering and technology-oriented students that didn’t necessarily expect daily frills and luxuries, such as made-to-order coffee, a dining menu with an international flair or conference rooms with leather chairs.

Those things came four decades later, after the original building had a $120 million upgrade and renovation that began in 2011 and was completed in 2015, making Talley the unquestioned center of student life on campus. Its standing was enhanced by the consolidation of student services with the creation of the Division of Academic and Student Affairs 10 years ago.

With the reopening of Reynolds Coliseum after a two-year renovation project in 2016 and the addition to Carmichael Gymnasium that opened in 2021 as a primary home for Wellness and Recreation, Talley is now the central hub of student activity it was originally intended to be, a place where prospective students visit as many as five times before they ever enroll at NC State and a place students, faculty, staff and other visitors can’t miss on their daily movements around campus.

Its 283,000 square feet of open space can be both active and calm, loud in the middle and quiet on the edges, with services that touch all members of NC State’s rapidly growing student population.

The modern Talley, after a half-century of evolution, is a strong embodiment of creating a clean, safe and welcoming atmosphere for the university community.

“That’s the heart of it for me,” says Tim Hogan, the director of NC State’s Student Centers.

The University Student Center

A surge in student enrollment shortly after State College became NC State University in 1965 created a need for more student activity space than could be provided by Erdahl-Cloyd Student Union that opened in 1954 adjacent to D.H. Hill Jr. Library and the Brickyard.

A lack of expansion space on the north side of central campus led the Physical Plant planners to select a parking lot between Reynolds Coliseum and the Student Supply Stores as the home for the new student center and an adjacent wing for the university’s music department (now Price Music Center).

“We are pleased with the way the building turned out,” said Henry Bowers, then director of the student center, when it quietly opened on June 1, 1972, some four years after it was first expected to be done. “There are a lot of problems to be worked out, but the summer will provide time for a shakedown cruise.”

Construction delays, cost overruns, a couple of failed inspections and questions over the funding of the $4.5 million, four-story building made for a rough and unfinished debut when students returned that August for the 1972-73 academic year. With out-of-state and graduate-student enrollment in steep decline and a looming energy crisis and deep recession, the pool of 12,761 enrolled students mostly from rural North Carolina were value-conscious in their educational goals.

Still, the original University Student Center was underwhelming, especially for the older students who had been patiently paying for a new center through their student fees, which began at $25 in 1964. An additional $20 per year was tacked on in 1966 to pay for the student center and $9 more in 1969 to pay for the music center. Upperclassmen were not happy about the delays or the design of a building that was unavailable to them for most of their college careers.

“It fulfilled more of a purpose for the university and less of a purpose for the students, other than having some organizations located there,” says alum Jim Pomeranz of Cary, who was vice president of the student center, an elected position at the time. “It had no character.

“It was just a big old building.”

It also lacked the convenience of the former student union to the D.H. Hill Jr. Library, the Brickyard and other amenities students had grown used to since its opening in 1954. Even when organizations, such as the University Activities Board, student government and student publications moved to the student center, many in the campus population still spent a good portion of their time at the old Erdahl-Cloyd space, which maintained a popular barber shop, a game room, a newsstand and an ice cream parlor.

There were features that the old union didn’t have, including 813-seat Stewart Theatre, a large ballroom and a box office and information desk where students could pay all university fees. There was also cutting-edge technology that appeared on campus for the first time: the student center, the Supply Stores and Bragaw Residence Hall snack bars all installed newfangled heating devices called microwave ovens, making hot food and sandwiches readily available.

The crowning feature was the fourth-floor Walnut Room, a wood-paneled and carpeted cafeteria that looked over campus on two sides, offered line service through the week and was designed for gourmet dining on the weekend.

Initially, the student center also was designed with a basement tavern that would have sold beer to eager college drinkers, but the anticipated change in state law that banned alcohol sales on state property never materialized. Through the years, the basement had a game rooms and billiard parlor, a snack bar and, at one point, a full-service steakhouse that was part of the University Dining plan.

Four months after it opened, the center was $180,000 in debt because of state-mandated salary increases and an unanticipated utilities increase that doubled from $75,000 to $150,000 the building’s steam and electricity bill. Students were hit with an additional $20 fee in 1973-74 to pay for the shortfall.

Food service was obviously a big part of the new center. The campus’s first cafeteria, Leazar Hall, was shut down in 1970 and the Harris Cafeteria at the corner of Dan Allen Drive and Cates Avenue was shut down shortly afterwards. Technician called for a boycott of university food services because of the poor quality of the food and a unilateral decision to serve sandwiches at several snack bars around campus.

For two years students and administrators had a hangry debate over what outside company should serve those sandwiches.

In coming years, especially after the opening of Fountain Dining Hall in 1982, the heavy focus on food service to feed thousands of students every day made much of the center’s space obsolete for its intended purpose. The fourth floor was converted to offices and expanded student government spaces.

That allowed the center to create more space for student activities and the arts program that was a career-long emphasis of Vice Chancellor of Student Life Banks Talley Jr. In addition to the school’s thriving music and theater departments, the center for a time served as the home to the Gregg Museum of Art & Design.

For 40 years, the center was an established gathering place that created memories, mostly fond, for NC State’s always-growing student population, with annual events like the medieval-themed Madrigal Dinner and the Pan-African Festival, monthly blood drives and art sales. Stewart Theatre hosted concerts, lectures and other student-focused events.

Honoring University Pioneers

In 1990, the university answered the call for a stand-alone space for a new African American Cultural Center with the opening of the Student Center Annex, a similarly utilitarian three-story building not far down Cates Avenue from the University Student Center.

That annex of 44,500 square feet currently is the home of the African American Cultural Center, a thriving cinema that also serves as one of the 10 largest classrooms on campus, Student Media offices and the Jeffrey Wright Military and Veteran Services.

In 1995, the building was named Witherspoon Student Center in honor of Augustus Witherspoon, the second African American to earn a Ph.D. at NC State and the university’s first African American professor.

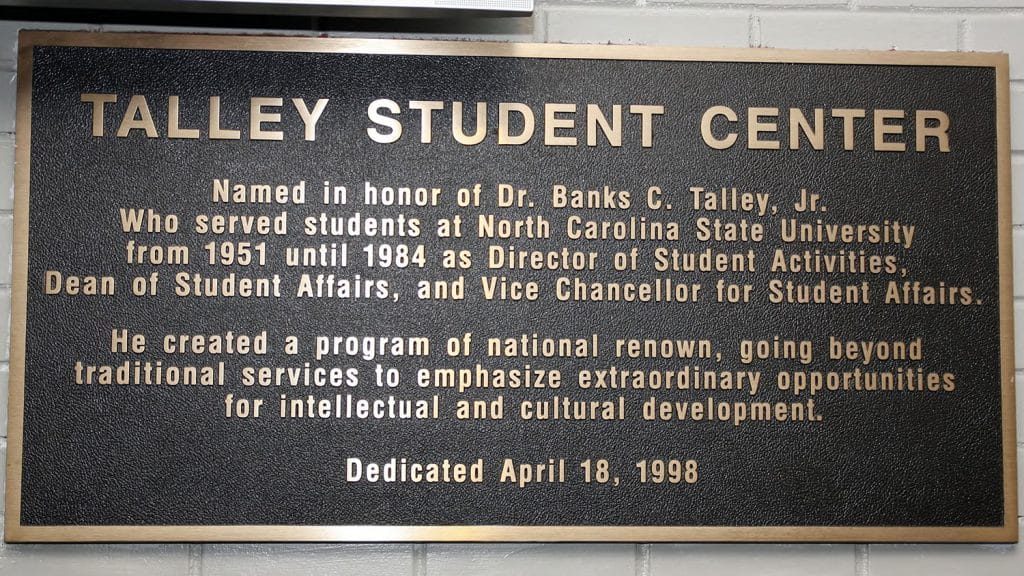

In 1998, following a push by Division of Student Affairs Director Thomas Stafford, the University Student Center was renamed Talley Student Center in honor of Banks Talley Jr., who had served at NC State in various student-focused positions since 1951 and was the university’s first director of student activities (eventually vice chancellor of student affairs) for 32 years.

Stafford arrived on campus in 1971 just before the new center opened, then succeeded Talley as director of student affairs when the longtime director took a one-year leave of absence in 1977 to become Gov. Jim Hunt’s first chief of staff and then retired in 1984.

I made it my personal mission to put his name on the student center.

“After he left, nothing was ever really done to appreciate the work he did or to recognize him in any way,” Stafford says. “That always bothered me because I knew what he meant to everyone on campus. So I kind of made it my personal mission to put his name on the student center, even though it was unusual for the university to name anything for a living person.”

Talley Student Center was officially dedicated on April 18, 1998, with Talley in attendance.

“I consider that one of the crowning achievements of my time at NC State,” says Stafford, who retired in 2012 and has remained on campus giving tours of NC State’s most beloved historical facilities.

In 2013, the large campus green adjacent to Talley was renamed the Thomas H. Stafford Jr. Commons.

The Modern Union

After more than four years of construction and renovation in two phases, the rebuilt original center was reopened as the Talley Student Union in 2013 and completed in the spring of 2015 in a flurry of activity.

Various campus departments, such as the Office for Institutional Equity and Diversity and Division of Academic and Student Affairs, along with the Women’s Center, GLBT Center and the Center for Multicultural Affairs, anchored the upper floors. Other groups, such as Multicultural Student Affairs, Greek Life, the University Graduate Student Association and Student Government also found new homes there.

Stewart Theatre remained largely unchanged, but received an upgraded stage, new seats and better lighting and a larger home for Arts NC State.

The updated union had three times more ballroom space and five times more meeting space. Two fireplaces were added on the main floor to create cozy study spaces on the building’s outer perimeter.

Then and Now

Starbucks, 1887 Bistro and Wolfpack Outfitters, the primary location for NC State Bookstores, opened later that summer. Talley Market, a convenience store located on the main floor, not only has basic grocery items, but is a major outlet for Howling Cow, NC State’s branded homemade ice cream.

Each of the five floors has open and hidden study spaces and gathering places for prospective students, current students, faculty and staff and a multitude of visitors that come to campus every day.

The union now employs 35 full-time staff members at both Talley and Witherspoon, three graduate assistants and more than 100 part-time students in a robust student employment system, more than double the number it employed when it first reopened and a long, long way from the three full-time employees that added to the debt initially accrued by the student center when it was completed in 1972.

“We are a small but mighty crew,” Hogan says.

Among the changes that have been made since the reopening are making Talley the starting place for Enrollment and Management Services’ prospective student visits and NC State’s popular Office of Global Engagement.

While the recent pandemic exposed the need for some technology upgrades to support remote learning, Hogan says Talley is strongly positioned to continue its role in being the central hub for student experiences on NC State’s campus.

“I think shared communal space where folks can come together is critical,” he says.

The Union’s Future

Historic industry standards of 10 square feet of space per student suggest NC State’s population — which will swell to over 40,000 undergraduates, graduate students and PhD. candidates in the next five years — needs more student union space.

“We realized almost as soon as we opened [after the 2011-15 renovation] that we had already run out of space,” Hogan says. “It’s a good news, bad news situation. We have the space, but with the number of events and meetings we have on a daily basis, the number of people we have here hanging out, studying, meeting, whatever, it’s not enough.

“It’s not a negative that people want to be here.”

Shared communal space where folks can come together is critical.

Along with a new strategic plan that again focuses on student success, the new Physical Master Plan is exploring such things as more spaces for student services and activities on Centennial Campus. And it’s looking at options to transform Cates Avenue into a pedestrian-focused thoroughfare to better connect Talley and Witherspoon.

“Right now, Witherspoon is a transactional facility in the same way Talley was when it first opened,” Hogan says. “Mostly the students who use those services or attend classes there use that building on a daily basis.

“But it’s not the same experience as Talley.”

There is expansion space, Hogan says, behind and around Witherspoon without infringing on the greenspace created by Harris Field in front of the building.

“That strategy has worked pretty well over the years,” Hogan says. “Right now, there are student demands for services that are not being met that could be addressed with additional space in Witherspoon.”

The future, of course, already has begun, as NC State welcomes the largest freshman class in university history this fall.

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: