Reclaiming Their History

The College of Design is bringing help to Princeville, N.C. as the town rebounds from floods and write its next chapter. But will it be enough?

In recent years, Princeville N.C. has been ravaged by hurricanes. As residents leave the town — the first in the nation incorporated by African-Americans — NC State professors and students are helping the community chart a path to the future.

PRINCEVILLE, N.C.— The town hall here is still closed, as is the senior center and the local history museum. It’s been that way since 2016, the last time a hurricane caused the Tar River to overflow its banks and pour into this small town in eastern North Carolina. There are signs of life here — the crew tending to the equipment at the volunteer fire department, a couple of churches that hold services on Sunday mornings, and customers buying milk, bread and cigarettes at Bridgers Food Store — but there are also enough weed-filled vacant lots and abandoned buildings to suggest that the town’s best days are behind it.

There’s a single roadside historical marker in Princeville. It stands in the middle of a small flower bed, an indication that civic pride was not completely washed away by the flooding caused by Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Floyd in 1999. A couple of concrete benches sit nearby, there for anyone who wants to take a few moments to consider the town’s early days. The sign says simply, “Community established here by freed blacks in 1865. Incorporated as Princeville in 1885.” What the sign doesn’t spell out is that Princeville is the oldest town incorporated by African-Americans in the United States. Or that the town’s history, and the connections many people feel to their ancestors, is why some people are not willing to give up on Princeville.

Let’s say Jamestown got wiped out by flood and hurricane. Would we walk away from Jamestown? No, because it’s essential to our understanding of American history, right?

Those people include Kofi Boone and Andy Fox, professors of landscape architecture at NC State’s College of Design. They, along with a handful of colleagues, are determined to help the roughly 1,900 people who still live here figure out ways to breathe new life into their town. Their efforts range from the simple act of planting flowers and bushes in front of town hall to working with town leaders and residents to develop ambitious plans for how to best use vacated land. They have no use for suggestions, frequently heard when the town finds itself in the news after a storm, that residents should move on before flood waters come again.

“What’s the oldest colonial American settlement?” Boone asks from his office in Brooks Hall. “Let’s say Jamestown got wiped out by flood and hurricane. Would we walk away from Jamestown? No, because it’s essential to our understanding of American history, right?

“Well, what if I told you that within driving distance is the oldest African-American town in the United States? Then it becomes a question of values. It’s not a question of capability, or skill or know-how. It’s a question of mind-set, and that we have this map of the world and what’s important and what’s not.

“And,” he says, speaking of Princeville, “they’re in the what’s not.”

Boone, Fox and others want to help the residents of Princeville change that, even if the odds can seem insurmountable. “When you think about a place like Princeville,” says Fox, “you’re talking about land that those formerly enslaved people — who didn’t even own their bodies — now they own land. And that’s been carried on for seven generations, and now I’m here and it’s my decision to let go of that? I don’t think so. If I were put in that position, I would hold on to it at all costs.”

I’m Rooted Here

Sometimes, though, the reasons for staying have more to do with the practicality of the matter, not to mention the cost and inconvenience of moving.

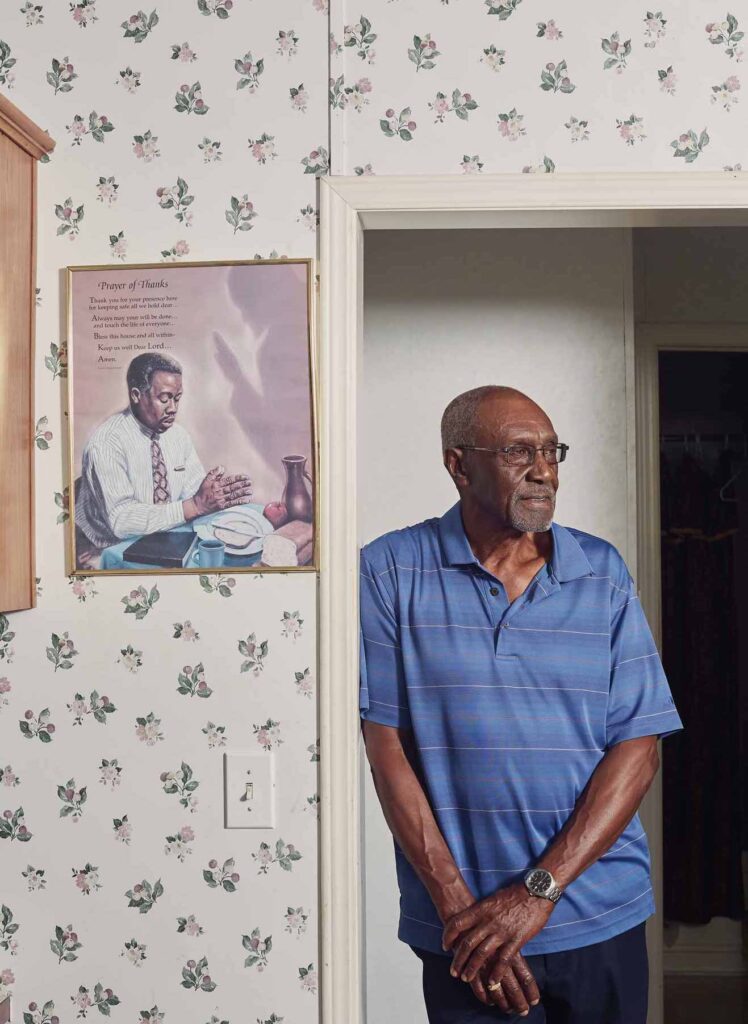

Roger Southerland, 76, a former mill worker, has lived in Princeville through Floyd and Matthew. He used proceeds from his flood insurance to build a new home after Floyd hit and then survived Matthew with relatively minor damage. But Matthew wreaked greater havoc on Princeville, and Southerland’s corner of town is now dominated by lots left vacant by residents who decided to move.

I feel like I’m rooted here. I feel like this is where I belong.

Southerland, who raised four children in Princeville, insists he is here to stay — at least as long as his health holds up. Despite being visually impaired, he keeps the street clear of fallen branches and other debris and uses a riding mower to keep the right-of-way neat and tidy. “I feel like I’m rooted here,” he says. “I feel like this is where I belong.”

Delia Perkins was Princeville’s mayor when Floyd hit in 1999 and water filled her house to the ceiling. Help poured in from all over the country, and Perkins met with President Clinton and the head of FEMA. More than $14 million was spent to help the town rebuild, and things had pretty much returned to normal before Matthew hit in 2016. She only had a couple of feet of water in her house that time, but the town has struggled to recover since then. But, at 77, Perkins can’t imagine calling anyplace else home. “You can go somewhere else, but if I was in Oklahoma, I might be knocked over by a tornado,” she says. “It just happens.”

NC State is not developing plans to stop future flooding — that’s a far more complex and expensive undertaking for engineers and elected officials to figure out. Instead, the professors are using their experience with landscape architecture — and its emphasis on connecting people with their environment — to help resource-strapped communities like Princeville and Lumberton figure out ways to cope (and even thrive) despite the threat of flooding.

You can go somewhere else, but if I was in Oklahoma, I might be knocked over by a tornado. It just happens.

It’s why Fox and Boone were willing, along with a crew of students, recent graduates, local officials and residents, to spend a day this summer digging up a plot in front of Princeville’s town hall and planting trees, bushes and flowers to make the entrance along Main Street more inviting, even if the building is still closed. Or that a group of architecture graduate students spent the summer designing and building a mobile history museum that Princeville can use to share its story with anyone willing to take a few minutes to listen. Or that NC State worked with the N.C. Department of Transportation to install signs this fall that would, at long last, let people know when they have arrived in Princeville.

“If more people know their story,” Boone says, “they will be more willing to share, partner and develop resources.”

Those are just the most recent— and most visible — indications of the work that NC State is doing to help Princeville rebuild. Boone and Fox also have helped some younger activists eager to revitalize the town —including a former player for NC State’s women’s basketball team —launch a nonprofit that can raise funds to host events to draw people to the town. And the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, a community development initiative focused on eastern North Carolina that Fox runs along with David Hill ’96, ’97, head of the college’s School of Architecture, recently received a grant to develop a comprehensive plan for how to make effective use of vacant and abandoned lots within Princeville.

“This lets people know that we have not been forgotten,” says Princeville Mayor Bobbie Jones ’10 MR, who joined the group from NC State on the day they planted flowers in front of town hall. “And that there is hope for the future.”

A Trust Issue

Few communities have struggled like Princeville. The community was initially called Freedom Hill to mark the spot (more of a slight rise, really, than a hill) where Union soldiers informed a group of blacks in 1865 that they were no longer slaves and were free to establish their own homes. The community they built was incorporated two decades later as Princeville, in honor of a former slave and carpenter named Turner Prince who built several of the town’s first homes. But like many African-American communities, the land available to Princeville’s first residents was marshland that made much of it unsuitable for agriculture and, as later years would prove, susceptible to flooding from the Tar River that separated the town from Tarboro. Before Floyd swallowed up the town in 1999, the town had been hit by floods or “high water” on at least five other occasions since its founding.

Boone and Fox are drawn to using their expertise and experience to help hardscrabble communities like Princeville, places that face similar challenges to the working-class streets of east Detroit where Boone grew up and the isolated farm in rural Michigan where Fox was raised.

Through the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, Fox focuses his efforts on the eastern North Carolina communities between the coast and Interstate 95 that have been hit hard by harsh new economic realities with the decline of tobacco farming and other agricultural jobs and a changing climate that has repeatedly brought what would normally be considered once-in-a-lifetime floods. While the attention during hurricanes is often on communities along the beach, Fox argues that it’s often towns well inland that are hit the hardest — and that have the fewest resources to rebuild. “Their position in the landscape is there because there was opportunity and the river was the highway, and that’s how commerce worked,” Fox says. “But, over time, that’s changed.”

There’s a trust issue in a place like Princeville. They have not been treated well for centuries.

Princeville residents have experienced their share of broken promises, as well as groups that move on quickly after the initial clean-up is completed. And then there are all the “experts,” eager to tell them what they need to do with their town, their homes, their community.

“There’s a trust issue in a place like Princeville,” Fox says. “They have not been treated well for centuries.”

The NC State team has approached Princeville and its residents differently. The professors didn’t show up after the storm saying they had all the answers, but instead offered their expertise to help make the community’s collective desires become a reality. They did that by listening, beginning with a five-day workshop in 2017 that invited local leaders and residents to spend time with a team of landscape architects and other experts from NC State and elsewhere. “They said, ‘Let us help you guys out. Let us undergird you,’” recalls Linda Joyner, one of Princeville’s town commissioners.

It is an approach embedded in the DNA of the College of Design, and one that Boone has used successfully in other communities, including New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward as it continued to struggle to recover from Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

But energy, no matter how positive, has to be sustained in a community that has suffered as much neglect as Princeville (or the Lower Ninth Ward) has through the years. Boone and Fox recognized that the problems they hoped to address wouldn’t be fixed overnight, and committed to working with Princeville for as long as necessary, and for as long as their efforts were welcome. That commitment was clear on a rainy day this summer, when the town unveiled the new mobile history museum. The exterior of the structure shouts out Princeville’s name and the year it was incorporated, serving as a rolling billboard for the town. It was the first structure to be built in Princeville since Matthew hit in 2016, and several local officials and residents turned out despite the weather to see the new museum. (More good news would come later in the evening. The assembled group was told that a contract had just been signed for the restoration of the town hall and that proposals to restore the former museum would go out for bids soon. They were also told that Princeville Elementary School would be reopening in January after being shuttered for three years.)

Kendrick Ransome, a local farmer who has been involved in efforts to revitalize the town, was one of the first to see the mobile museum when Randy Lanou ’97 MR, one of the class instructors, and graduate student Elenor Methven ’19 MR delivered it to town a week before the unveiling. Ransome pulled over and hopped out of his car to get a closer look. “This is dope,” he says. “Man, this is awesome. This will draw some attention to Princeville. This is exciting, to get some history in here.”

Be The Change

Before they could design a new mobile museum to tell Princeville’s story, the students paid a visit to check out the town for themselves.

“It was pretty shocking to see the condition of the town,” says Ross Davidson ’12, ’19 MR, who admits he had never heard of Princeville before taking the class. “Half the houses are abandoned. It’s like an episode of The Walking Dead.”

But the students found the inspiration they were seeking. Their guide for the day is Milton Bullock, one of Princeville’s town commissioners. But his primary claim to fame is his former career as a member of The Platters. His small house on the edge of town is filled with memorabilia from his career, including photos with celebrities like Muhammed Ali. He is always ready, it seems, to share a story from his career or burst out into song. At 71, Bullock still has the smooth voice of a professional crooner.

Today, though, Bullock is ready to show the students from NC State around his town. Bullock grew up in Princeville and then moved back after Floyd to save the family home — FEMA would not rebuild the home unless a member of the family lived there, and Bullock was the only volunteer. “I’d been around the world three or four times [with The Platters] and done everything I wanted to do,” he says. “Now, maybe I can contribute to my community and share some of my wisdom and knowledge.”

He initially planned to take a buyout from FEMA after Matthew, deciding that he didn’t want to risk another flood. But he changed his mind, and now seems determined to make sure everyone learns Princeville’s story. Bullock greets the students wearing a brimmed straw hat and a flowered shirt, tied up to reveal his mid-section, his response to the searing summer heat. “You are standing on hallowed ground right here,” Bullock tells them as they gather around the historical marker so he can share the story of the town’s founding by freed slaves, some of them Bullock’s ancestors. Later, Bullock leads the students down a boat ramp to a spot on the Tar River known as Shiloh Landing (or Shiloh Point, depending on who’s telling the story). Local legend has it that slaves were once brought to this bend in the river by barge to be unloaded. He tells them the students are standing on “one of the holiest” places in the area.

The students listen and snap photos with their phones, but some of them are distracted by another visitor to the river. Marquetta Dickens ’07, a former NC State basketball player, is the granddaughter of Perkins, who was Princeville’s mayor when Floyd hit. She is now an assistant athletic director and the head coach of the women’s basketball team at the College of Saint Elizabeth in Morristown, N.J., but she returns home to Princeville regularly to see her grandparents.

She is also working with Ransome, a local farmer, to bring new vigor to Princeville. They both talk about their days as children in Princeville —riding bikes, going fishing, playing basketball — and note the absence of kids doing the same today. They recognize that young families need compelling reasons, not to mention jobs, to decide to make Princeville their home. They have worked with Boone and Fox to establish a nonprofit group that can raise money to sponsor events in town, including a homecoming celebration planned for this August.

Their efforts are welcome to Boone, who says Princeville has to find a way to appeal to younger people. “There’s a generation gap in Princeville,” he says. “My hope is that some of this will start to erode that generation gap.”

Several of the students gather around Dickens and Ransome, asking what they would like to see in a mobile history museum. (Funding still must be secured to develop exhibits for the museum’s interior.) But first, Dickens wants to let the students know how grateful she is for their efforts. “This is important,” she says. “To see people from outside of our community, it means a lot.”

Dickens then tells the students that she never knew the story behind Shiloh Landing, and that she used to tell people she was from Tarboro because that was where she went to high school. “Now, I’m from Princeville,” she says. “Princeville is too important to die.” She says the museum needs to share the story of the town’s past, its present and its uncertain future. She imagines it traveling to historically black colleges and universities, while others talk of it being taken to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. “This whole thing has potential,” Bullock says. “Princeville has been exploited in so many ways.”

Dickens agrees, but adds, “We have to be the change.”

Before the group heads to the next stop, one of the students pulls Dickens aside. Toneisha Mathis ’17, ’19 MR, who is one of only two African-American students in the class, talks with Dickens about walking down to the water’s edge to take in the surroundings and what once took place here. “Do you feel something when you’re here?” Mathis asks.

“I do,” Dickens responds.

— Bill Krueger

Photography by Justin Cook

This story appears in the winter 2019 issue of NC State magazine. Members receive the award-winning publication in their mailboxes every quarter.