An Extreme, Unusual 2020: The Weather Year in Review

Note: This is a guest post from Corey Davis, Assistant State Climatologist of North Carolina, and Kathie Dello, State Climatologist of North Carolina and director of the North Carolina State Climate Office at NC State University.

The unprecedented aspects of 2020 included our climate in North Carolina, which the statistics show was an extreme year in our modern history.

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, 2020 was our second-wettest year on record and tied for our third-warmest year on record dating back to 1895. That makes 2020 the only time in the past 126 years with both our annual temperatures and precipitation ranked in the top five.

Perhaps more unusual than the rankings themselves is the story of how we got there: a persistent warm and wet pattern that was defined not by a single event, but by the sum of its parts:

Abundant moisture from an active tropical Atlantic. Amid a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season with 30 named storms, only one storm – Isaias in early August – directly made landfall in North Carolina. However, the remnants of at least eight other systems moved through our state, beginning with Arthur and Bertha in May and continuing through the fall with storms like Sally, Delta, and Zeta that originally made landfall along the Gulf coast.

The influx of tropical air and moisture from these storms meant heavy rainfall and flooding, from the beaches along the Outer Banks to the streets of Asheville. And storms didn’t even need to move through North Carolina to have significant impacts. In mid-November, Tropical Storm Eta fed moisture to a cold front that produced nearly 10 inches of rain across the western Piedmont and the northern Coastal Plain.

Severe weather, in and out of season. Climatologically, most of our severe storms and tornadoes occur during the spring, but in 2020, these storms started early and lasted throughout the year. The National Weather Service confirmed 48 tornadoes across the state last year, which ranks as the sixth-most since 1950. The first tornadoes formed in early February from a line of storms crossing the southwestern Piedmont, and activity picked up during the April 13 outbreak.

During the summer and fall, 21 tornadoes were spawned by tropical systems or their remnants, including 14 from Isaias with the strongest at EF3 intensity causing two deaths and 14 injuries in Bertie County. To end the year, we even had a Christmas Eve tornado in Columbus County associated with a cold front that raced across the state that day.

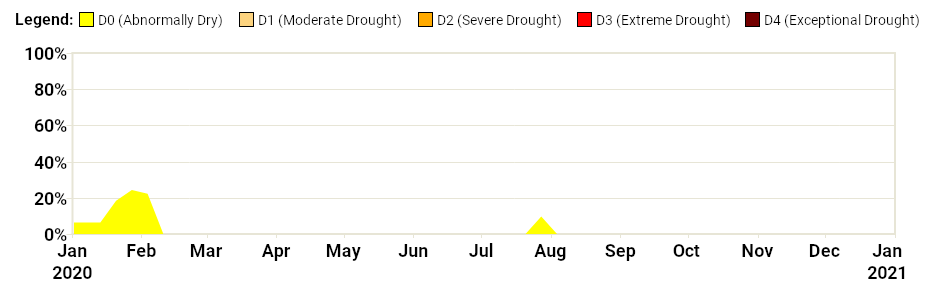

Regular rainfall and rising rivers keep us out of drought. With so many impactful weather systems hitting in quick succession throughout the year, rivers and streams had little time to recover, which caused some notable crests across the state.

In Rockingham County, the Dan River near Wentworth recorded three of its top ten all-time highest crests last year in February, May, and November. The Neuse River at Kinston spent much of November in flood stage and reached its seventh-highest crest on November 20.

Perhaps most impressive of all, the Tar River at Rocky Mount recorded its third-highest crest on record, behind only the floods from hurricanes Floyd and Matthew. The latest high water mark wasn’t from a tropical storm, but after slow-moving summer showers added more water to the already-full river on June 18.

Such wet weather meant drought never developed in the state during the entire calendar year, which was only the third such occurrence (along with 2003 and 2014) since the U.S. Drought Monitor began classifying conditions in 2000. Even with two months of hot, humid weather in July and August, our rainfall remained frequent and widespread enough to avoid any sustained dryness.

Our warm, wet weather also had impacts on weather-affected sectors across the state, both for better and for worse.

For agriculture, the growing season started early with unseasonably warm conditions in February and March, but spring freezes in our northern and western counties on April 11 and May 10 caused minor damage to early-emerging crops. After that, wet fields were the main story of the growing season, with localized flooding and a delayed cotton and soybean harvest in the fall.

Wildfire activity was held down by the wet weather. The NC Forest Service reports a preliminary annual total of 2,354 wildfires, which would be the 11th-fewest dating back to 1928, and 7,704 acres burned, which would be the fewest on record.

Water systems had too much of a good thing: excess rainfall meant reservoirs remained full, and at sites like Fontana Lake, in the mountains, heavy rains in the spring and fall caused lake levels to spike well above their normal seasonal elevations.

So what made 2020 so extreme? Unlike our wettest year in 2018, which included the record rainfall and floods from Hurricane Florence, or our warmest year in 2019, in which summer heat persisted through early October, it’s tough to point to a single event that made 2020 so unique.

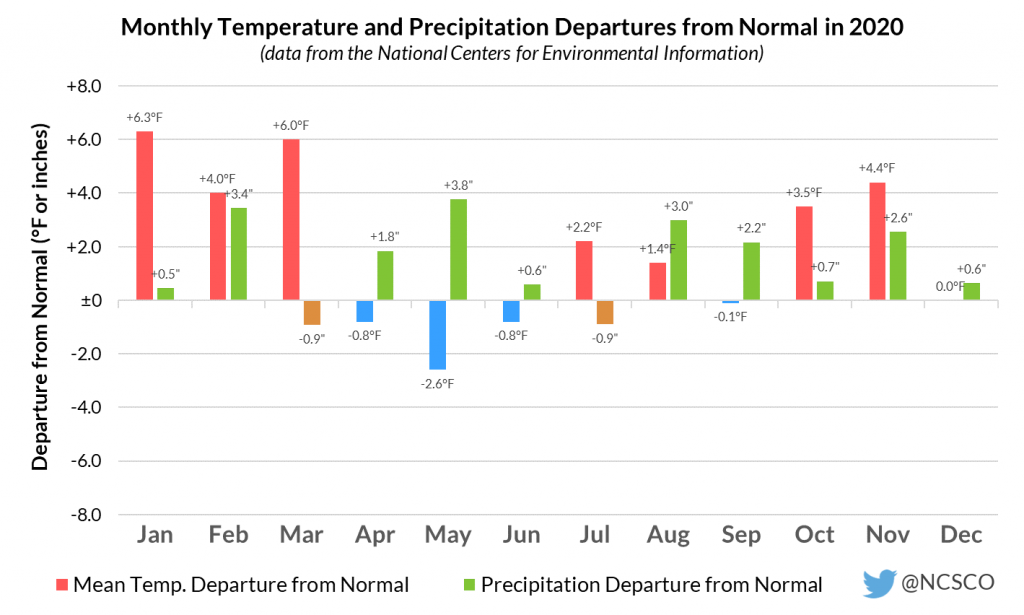

Instead, it was the additive effect of many warm and wet months with few cool and dry ones. We began the year with a warm winter and early spring, only briefly cooled in the late spring and early summer, then saw the heat pick up in the summer and fall as tropical air masses moved in from the south.

Just two months all year — March and July — were drier than normal statewide, and an overall wet pattern beginning in May saw both tropical and non-tropical weather systems bring in ample moisture and heavy rainfall.

Our climate is indeed becoming warmer and wetter in North Carolina, and 2020 is the latest example of that. Seven of our state’s ten warmest years have occurred since 2007, and extreme precipitation events with more than 3 or 4 inches falling in a single day are becoming more common in a warmer and more humid environment.

Nighttime low temperatures continue to show some of the most noticeable changes, and 2020 was the sixth consecutive year in which we’ve tied or broken our record for the warmest minimum temperatures.

These warmer nights have consequences for both plant and human health, from fruit crops not accumulating enough chilling hours during the winter to increasing heat stress for outdoor workers and areas without sufficient access to air conditioning. As 2020 showed, these warming nights are a trend that shows no sign of reversing.

For more about climate change and its impacts in North Carolina, check out the state’s official Climate Science Report. And for more on our weather in 2020, the recording of our recent Year in Review Webinar is available for viewing.

This post was originally published in NC State News.